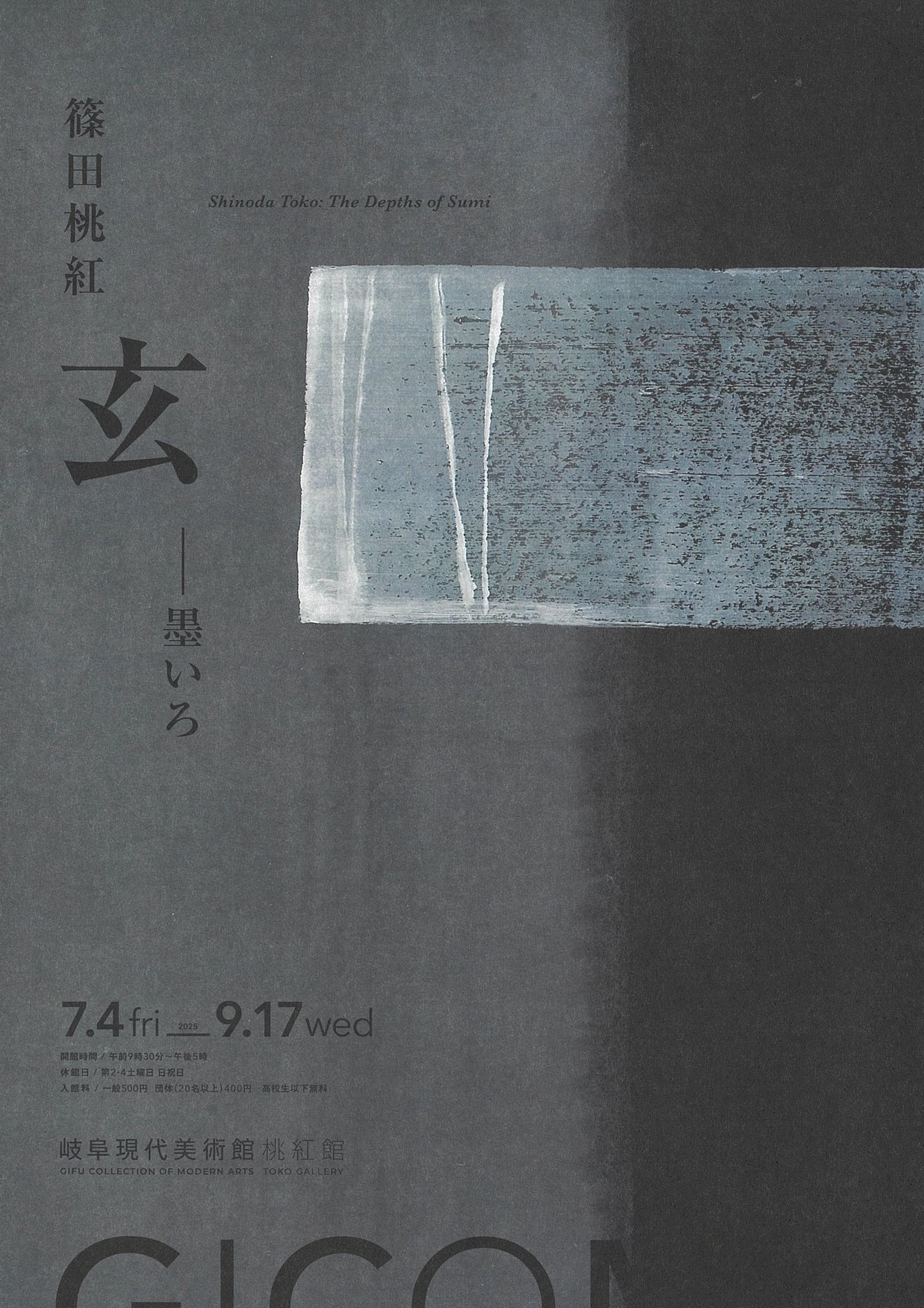

Current Exhibition

Shinoda Toko: The Depths of Sumi

Hours

AM9:30 — PM5:00

Address

1, Toko-taichi, Seki-City, GIFU 501-3939, Japan

phone: +81-575-23-1210

fax: +81-575-23-1218

Closed

Sunday, 2nd and 4th Saturday, public holiday

Admission

Toko Gallery:General 500 yen, High school students and younger: Free, Group rate (20 or more people): 400 yen

*Admission free for visitors with disabilities and one attendant. (Please present certificate at the admission.

Taichi Hall:Free

Visitor Guidelines

- Please do not touch the exhibits.

- Photography is not permitted inside the museum.

- Please refrain from talking, eating, and drinking (including gum and candy) inside the exhibition rooms.

- The museum is a non-smoking facility.

- Bringing animals, plants, hazardous materials, and umbrellas into the museum is not allowed.

- The use of writing instruments other than pencils is prohibited in the exhibition rooms.

- The museum maintains a constant temperature and humidity for the protection of the artworks.

Access

[By Train]

From JR Gifu Station 30 minutes by taxi

From Meitetsu Shin Unuma Station 20 minutes by taxi

From Meitetsu Mikakino Station 15 minutes by taxi

From Seki City Terminal 12 minutes by taxi

[By car ]

Approximately 5 minutes from the Seki I.C. of the Tokai-Hokuriku expressway

Audio Guide Information

Audio explanations are available for some of the works in the atelier and exhibition rooms.

Guests can access free audio guides via the museum's WiFi.

Please note that we do not offer rental audio guide devices. If you wish to use the audio guide, please prepare your own smartphone and earphones.

Please note when using the audio guide

- Bring your smartphone and earphones, and enter the exhibition room.

- Use earphones or headphones when listening inside the exhibition rooms.

- We do not offer smartphone or earphone rentals (earphones are available for purchase at the reception if you do not have your own).

- Recording of the audio guide is prohibited.

Dialogue between Toko Shinoda and Taichi Okamoto

(Taichi Okamoto is former director of the Gifu Collection of Modern Arts Foundation and chairman of ...